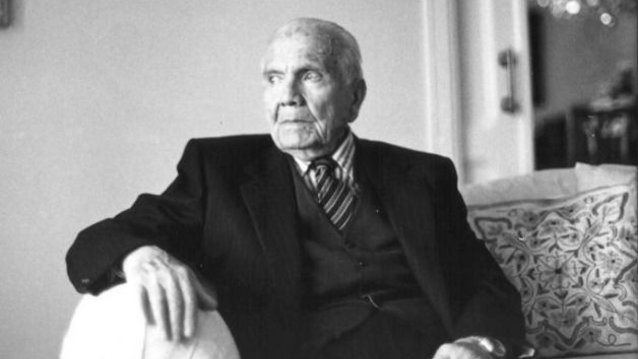

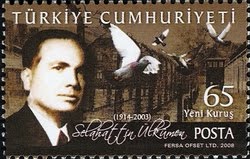

Answering the question of what made him a hero, Turkish diplomat Selahattin Ülkümen is once said to have responded: “All that I did was follow my obligations as a human being.” A rather humble answer for someone who had saved the lives of 42 others, and who, in 1990, became the only Turkish citizen to be recognized in the Israeli Holocaust Remembrance Centre Yad Vashem as “Righteous among the Nations”. The recognition of “Righteous among the Nations” is given to those that took personal risks to save Jews from deportation between 1933 and 1945.

As a young man, Ülkümen was the Turkish Consul on Rhodes Island. The island in the South Aegean Sea had been a part of the Ottoman Empire for almost 400 years when it was occupied by troops of the Kingdom of Italy in 1912 during the Ottoman-Italian War. In the early 1940s, 3,700 mostly Sephardic Jews were living on Rhodes. Many of them already fled during the reign of Fascist Italy. When dictator Benito Mussolini was overthrown in 1943, Italy agreed to a cease fire with parts of the Anti-Hitler coalition; the German Wehrmacht occupied Rhodes, where around 1,700 Jews were still living.

Cheering citizens of Rhodes after the liberation of the island in 1945. Credits: Hawkins Trevor J (Sergeant)

Cheering citizens of Rhodes after the liberation of the island in 1945. Credits: Hawkins Trevor J (Sergeant)

Ülkümen’s List

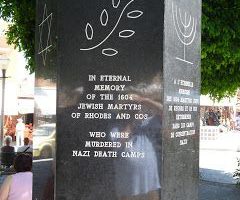

In Mid-July of 1944, Ulrich Kleemann, German Commandant of the East Aegean, ordered their arrest and deportation to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Thanks to Ülkümen’s intervention, at least 42 Jews were spared this fate.

Ülkümen, at that time just 30 years old, first issued Turkish documents for those who had once been Ottoman nationals. He then claimed to the Germans that there was “a Turkish law that states the spouse of a Turkish national is automatically a Turkish national”, said survivor Matilda Toriel. Such a law did not exist; Ülkümen had invented it to fool the Nazis and protect the Jewish spouses as well.

This was not enough: As the German ruling powers believed that all Jews were to be deported in spite of their citizenship, Ülkümen threatened to call on the Turkish government if those with Turkish passports were not released. It was a successful bluff : The Nazis at that time apparently sought to avoid a conflict with Turkey – there were still diplomatic and economic ties between the countries. Consequently, all those whose names were on Ülkümen’s list gained their freedom and were spared from deportation.

Ülkümen’s actions were doubly valiant. On the one hand, he defied the German occupiers. On the other hand, as Turkish Consul, he also defied the protocols of the Turkish government. This had enacted a decree in 1938 that no foreign Jews were to be issued visas.

Not just a shining light

The neutral Turkish Republic barely shrouded itself in glory during World War II. In fact, its politics were “contradictory”, writes Turkologist Corry Guttstadt in her book “Turkey, the Jews, and the Holocaust”. Although the country granted persecuted Jewish German scientists and artists exile, it also did little to save its Jewish citizens who remained in the NS sphere of control.

Yet another chapter of World War II history shows this contradiction as well: in 1942, the ship Sturma sank near the coast of Istanbul with 781 Jewish refugees from Europe and 10 crew members on board; almost all passengers died. For weeks the passengers had been hindered from going ashore, despite horrifying conditions on board. Turkey did not want to take in the refugees. Great Britain, with whom the Turkish government was negotiating the issue of the Sturma, also did not want to grant refuge in its Palestinian mandate due to missing visas. The sad story of the ship without a haven was dealt with in several novels, like in those by Zulfü Livaneli und Doğan Akhanlı.

And: antisemitism existed (and exists) in Turkey. For instance, in 1934, there was a series of pogroms against the Jewish minority in the Thracian region that 15,000 Jews had to flee.

Heroism and humility

Selahattin Ülkümen stood for the other side, one of safety and courage. Aside from his recognition in Yad Vashem he received further honors. In 2003, Ishak Haleva, the current Hahambaşı (the Great Rabbi of Turkey), inaugurated a memorial plaque to Ülkümen in Istanbul. In 2012 a primary school was ceremoniously named after him in Van.

Ülkümen, who lived to be almost 90 years old in 2003, was asked about his motives countless times. One account of a declaration is: “In Islam it is as in Judaism; whoever saves the life of a man, saves the whole world. I would do the exact same again.”

EXCOURSE: Sephardi Jews and the Ottoman Empire

Sephardi Jews had been living in the Ottoman Empire since the late Middle Ages. They were taken in there after more than thousands of Jews were driven out under the Reconquista of the Iberian Peninsula and during the Inquisition between 1492 and 1513.

Today, the largest Jewish communities in Turkey are in Istanbul and Izmir. Synagogues, Jewish cemeteries, Jewish schools, and newspapers (for instance the bilingual newspaper Şalom Gazetesi, which is published in Turkish and Ladino – the Sephardi language) show that Jewish life that is inextricably linked with the history of the Ottoman Empire and Turkey. There are around 18,000 Jews living in Turkey today, 96 per cent of these are Sephardi. The numbers did decrease dramatically: in 2010 there were still 26,000, and in 1948, when Israel was founded as a state, there were 120,000.

At the end of the 19th century, there were around 400,000 Jews living within the Ottoman Empire. Due to the good relations between the Ottoman Empire and Europe, Turkish Jews emigrated to Central and Western Europe in large numbers. Turkish Sephardis lived in Berlin before and during the war, and there was a large Sephardic community in Vienna in the 1930s as well. Several thousand Jews of Turkish nationality or those stripped from their Turkish citizenship and made stateless, who had been living in Germany or France, fell victim to the Shoah.

Credits

Translation: Karin Louise Espejo Hermes

Cover image: https://historia.co.il/