BaBa ZuLa, the legendary ensemble from Istanbul, have brilliantly established themselves over the past two decades as the missing link between Turkish Psych, Krautrock and dub-wise Stylings. “Derin Derin” is the thrilling follow-up to their acclaimed retrospective “XX,” and finds the band more experimental and expansive than ever. renk. had the Chance to catch up with bandmember Murat Ertel.

About your latest album. What does it mean, “Derin, Derin”?

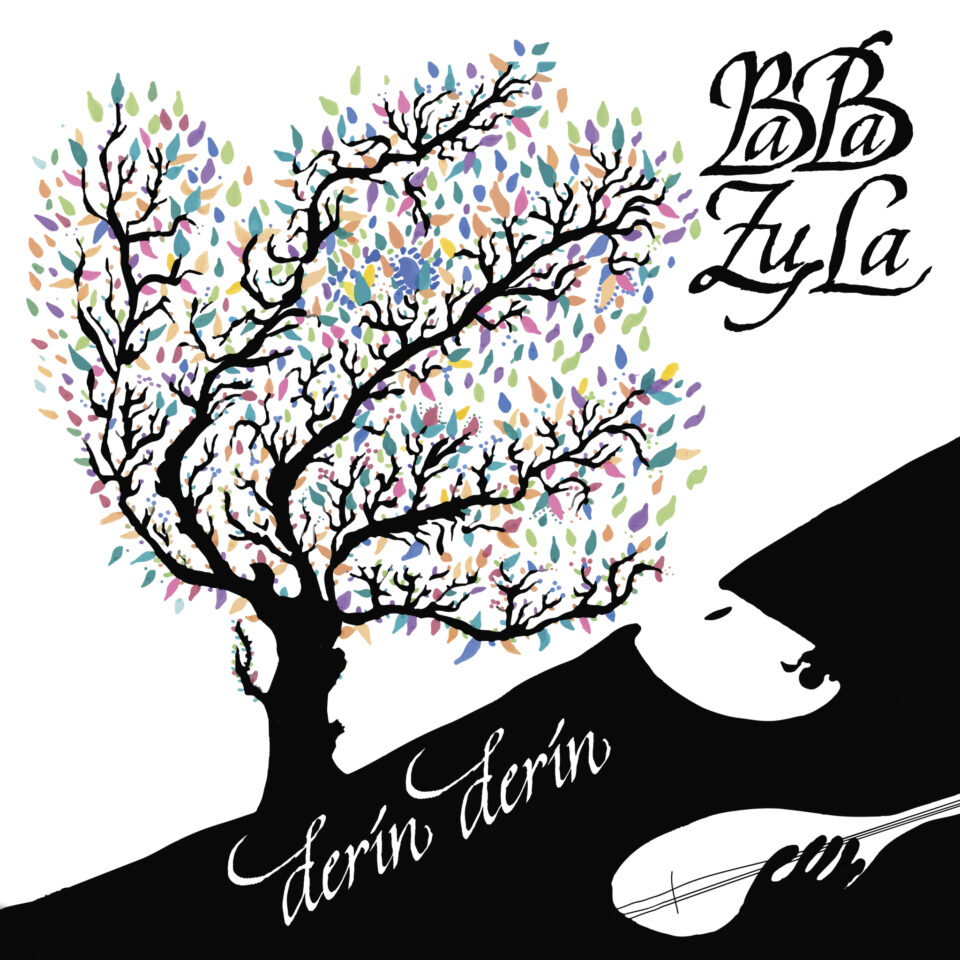

“Derin, Derin” is kind of like, “Deep and deeper”. If you see the cover, then you will understand better, I think.

There’s a tree on the cover.

Yes, it’s a tree. But not only a tree. There’s the earth and also an image of an Aşık – a troubadour musician – in the depths of the earth – kind of a symbolic thing going on. In the depths of the world and in Turkish culture, there is this figure of the Turkish Aşık. He or she used to come from the pre-Islamic days of Turkish people, from shamanic days, and this tradition continued. Those Aşık guys were telling the truth always.

They were against the palace, against the Ottomans, against the Sultans. They were the voice of the people. The Sultans were afraid of them and the most powerful of them were mostly killed. This tradition was kind of killed off in Turkey. It only lives on in subcultures. But they cannot stop it. Even if they bury them in the ground, this lifecycle based on earth, water and air will be taken by a tree and will blossom as leaves and fruits. And this deep cycle is going on and on. There will be another time when the truth twill be told.

So the tradition of the Aşıks, it doesn’t really persist today.

Not really. But for instance we can see that Baba Zula is kind of a secret, a secret heritage of this tradition. We are, I think, continuing this tradition. Not openly, but secretly.

What do you mean by secretly?

What our messages is – our lyrics and everything we do – has some level of secrecy in it. Not everyone can understand it. That’s how we survive. We survive in the deep, deep things. In the underground, or whatever you call it.

Do you get into any problems with the authorities in Turkey?

Yes, many times. I come from a family of artists. My uncles were artists and cartoonists and my father was a graphic designer. Starting from my childhood I was burning books and I was burning letters and burying books. I was watching for the police or the military men, and I would run and warn my father, “Hey police is coming now! Soldiers are coming!” Things like that.

I’ve seen all of them in prison and tortured, coming home with broken bones and bloody. I have seen my family like this. So, I take my precautions in transmitting my messages through art, kind of like hiding them with something, you know. You cannot just read or look at something that Baba Zula has done and understand it instantly. Or you would understand only a superficial portion of it. You have to dig deeper in the depths – Then you can see other levels.

What are your thoughts about the last elections in Istanbul?

Ah! It’s great! We are deeply, very positively affected by it. At first we couldn’t believe it. But this guy who was elected now (Ekrem İmamoğlu), we didn’t know about him. He was coming from a very small scale kind of a place. He was very successful, then he became a candidate for mayor for Istanbul, and he won. But the government played many tricks, and they lied and did this, that and the other, and they wanted to change the results.

In every election I think they have been doing this all the time. And now we know that they are masters of lies and manipulating votes. Now we know that maybe they never ever won an election squarely. Now people are really into stopping their evil ways and cheatings.

The album, is it in any way political?

Yes, I think so. Even the way we look – I read an article about Jimi Hendrix. They were asking, “Is Jimi Hendrix political?” And in this article it said, yes, he is political because, first he was not a white guy, but survived in the world of the white Anglo-Saxon guys as a half Native American, half Afro-American. And he wore all these clothes and he had this image. And so he was political. I can say this also about ourselves. And in all our subculture messages I think we are very political. But our politics does not only concern our region. I think it is for the whole humanity. This power thing, this capitalist thing. I think all the people are bored of it.

We don’t only have our dictator. The world is full of dictators and crazy leaders. Look at America, Russia, Italy or Hungary. So if we talk about something it’s not only about Turkey, but the world – humanity. We are also defending the rights of animals. And even plants. For instance, no one is talking about the rights of plants. We do. Because they have to be defended. Look at the Amazon, for instance. So many plants are becoming extinct from this world. So yeah, I think this album is a political one.

How did the new album come about?

Well, it first started as an instrumental. We were doing some music for a documentary about hunting birds. It was about hawks and eagles that were used for hunting by people. After doing music for this documentary we felt this lost connection with nature. Then, apart from these instrumentals, one by one some songs emerged. One is for instance “Portpass”, which is a kind of multi-linguistic song about our real experiences of being musicians and being a Turkish musician and going all around the world. This track is dealing with for instance visa problems, racism and coming from a country that is labeled as half-terrorist or whatever, being afraid of Islam, so many problems.

The lyrics come from our real experiences. Like having passport controls three times. When non-Turkish people are controlled, they are controlled only once. Sometimes Turkish people are controlled three times. It’s very interesting. When you get off the plane there are policemen sometimes waiting and they control your passports. It’s not like a legal control. Stuff like that. And there are love songs. And there is a song that my child sang to me and we did it together with him. This album is also a kind of very personal album.

What is the connection between Baba Zula and Krautrock?

Hmmm. Well, we like Krautrock. There are many connections with Baba Zula and different music genres. An obvious one is psychedelia. And another one can be dub. Another one can be like “Oriental music”, maybe.

In fact we didn’t know about Krautrock that much. We only knew maybe Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream. And those bands maybe you cannot call Krautrock that much. But in 1993, or something like that, I had another band called Zen, and one of our albums was chosen as best alternative album of 1993 by an American magazine called Spin. And in this article they were talking about a band called Can. They said our band was something like Can, or the people who like Can also might like us. So, that’s how we found out about Can.

Then by chance around the year 2000 we became friends with Jaki Liebezeit, the drummer from Can. He was a very, very influential musician for us. We became friends and he came to Istanbul many times and we went to Cologne many times. We played with him, we rehearsed with him and we learned many things from him and this was very influential.

Has Baba Zula’s lineup changed for the last album?

Yeah, I think we are going for a more experimental also more heavy way. Before we sometimes had a guest female singer. Now we are more a quartet and we are more close to the music that we love. Psychedelia of the late sixties. Bands like Hendrix Experience and Cream and stuff like that. So we are more happy with this sound.

Also I think it is very interesting that we have this combination of electric saz and electric oud, which kind of never happens. Together I haven’t seen a band using them. I think this range of frequencies has a really good balance. So I really like that with the new formation of the band. And live I think we are getting more powerful.

When Baba Zula got together the scene was Taksim. Apparently now it’s not anymore, but Kadıköy. Can you tell me about these changes?

Well, that was the plan of the government already, I think. They wanted to stop people getting together. And this Gezi moment was a big thing for the government because people did it, they got together in Taksim. The people kind of like invaded Taksim. There was no police force that could oppose them. So they wanted to destroy these people coming together in Taksim.

They built hotels there and it became like a concrete place that no one wanted to go to except Arab tourists. And so the youth had to find themselves another place, which is now Kadıköy. Also Beşiktaş is now the new alternative. After Kadıköy it’s going to grow up and be the next cultural center of Istanbul. But now when we go back and think, Taksim has gone through these changes almost like every one or two decades. So, a new change is going to come, but I think it is not going to come soon. But Turkey is a very unpredictable country.

And also Istanbul is like that. And also with this mayor for Istanbul everything can change because this guy is very clever and very positive and he says he’s going to do lots of revolutions in culture. And many artists love him. Me too. I love him. It’s been like twenty years or so that no one that I voted for has ever won. This is the first time that someone I voted for is winning. So this a great, big, big chance.

Tell me about the symbolism of your clothing.

I pay big attention to our costumes and our gigs have strong link with theatrics and rituals and ceremonies. The hat I wear is coming from Aegean Thracian region and has dionisiac roots paganic bachas as they say. This is related with zeybek culture or zeibekiko, as the Greeks say. It is the hat of a warrior, rebel of nature. The main costume or the skirt I wear belongs to the Alevite culture. It’s in a way a shamanic interpretation of Islam of the people of the fire where it goes back tens of thousands of years. It has many symbolic meanings.

Text: Robert Rigney

Photos: gülbaba Records/ E