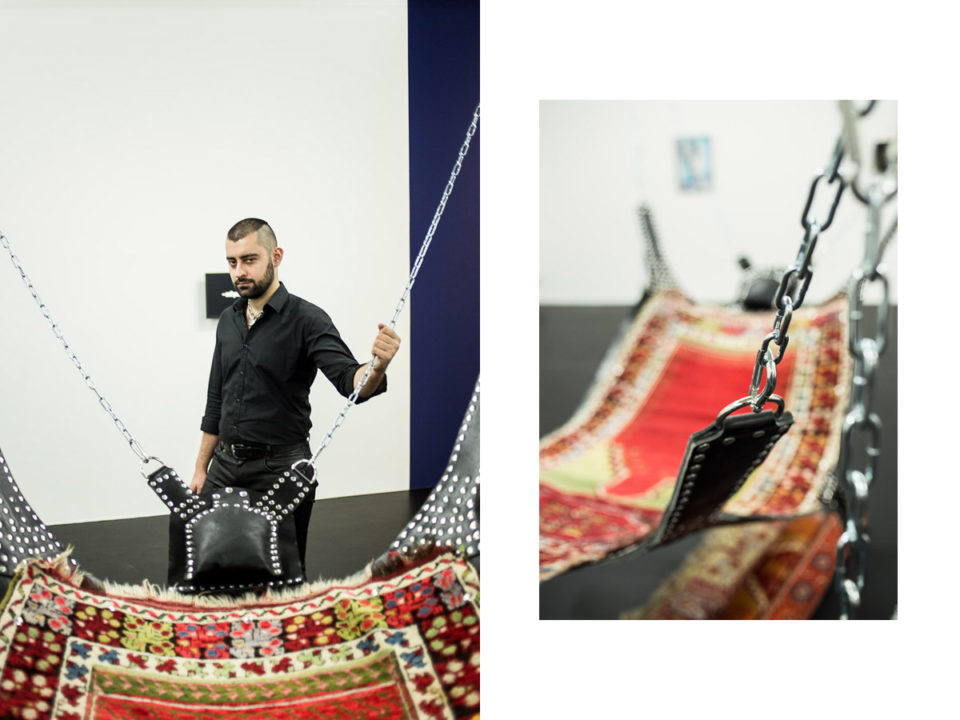

In the centre of the room, there’s an installation by Viron Erol Vert, a mixture of bondage-swing and flying carpet. A fusion which visually catches the theme of the whole exhibition in a nutshell. You’d like to lie down and resonate.

The new special exhibition ğ – queer shapes migrate in the gay museum in Berlin-Schöneberg illustrates the life experiences of queer migrants and takes a closer look at a chapter of Berlin’s cultural history which has received little attention in this way so far. The project by Emre Busse and Aykan Safoğlu includes works, created between 1997 and 2017, by artists from different generations who moved and still move between Turkey and Germany.

It’s not just the artwork, the details of the exhibition and the conscious connections all have stories to tell. The floor, so Emre tells us, is designed to show the footprints of the visitors, the way people leave footprints in the world when they migrate. This is true of Cihangir Gümüştürkmen’s portrait of Fatma Souad, female founder of the gay-lesbian oriental party series Gayhane in the Kreuzberger club SO36. The portrait of the glorious drag queen hanging opposite the video installation Am Haus by Ayşe Erkmen is not there by accident. The same building stands opposite the club SO36 in the Oranienstraße in real life, too.

The attention to detail, a sense of aesthetics and the medial variety makes this exhibition a lasting event and a small milestone in Berlin’s art scene. The title queer shapes migrate isn’t theoretical; it feels more like a statement saying these two attributes have always naturally gone together.

Emre, Aykan, where did you two meet each other?

E: We met in 2010 in Istanbul where I worked as an assistant for a director and Aykan was taking part in a group exhibition. A while later, after I’d seen saw his work, I just wanted to meet him. I contacted him and we started talking about collective projects. As our plans evolved, Aykan and I became friends.

What came first, the art or the concept?

E: We had a concept. We felt that the time was right for something like this to happen in Germany. Although I had no experience as a curator at all, the queer museum asked me to do a show for them. So I just thought: Okay, this is a great opportunity. These people have been part of this country for fifty years and no exhibition about the migration history of LGBT+ people in Germany has ever been shown. But we don’t want to be didactic, that’s why we decided to show contemporary art work and enrich the concept by adding further events.

Aber wir wollen nicht so didaktisch vorgehen, deshalb zeigen wir zeitgenössische Kunstwerke und bereichern das Konzept mit einem breiten Rahmenprogramm.

Apart from the fact that the Turkish letter is still mispronounced by a lot of Germans, what is the symbolic function of the letter ğ / soft g in this project?

E: It’s an unspoken metaphor, like a feeling, a smell or a voice. This letter can help us to transcribe pictures. In this way, we can inhabit the vowel.

A: This letter is marginalized, even though it is a basic letter in the Turkish alphabet. It helps other letters to resonate and, yet, is always neglected.

E: Aykan’s and my surnames actually include the soft g, as well. The names are from our fathers and gave us the chance to play with that. In Turkish slang it is also used to denote a gay person in a joking but humiliating way.

How do the events complement the exhibition?

E: This is art spiced with historical context, communication, performance and discussion. Our job was to provide the works of art. Visitors now have the chance to connect with the artists. Added to that are people like the activist Ebru Kırancı or the author Cem Yildiz with his new book Fucking Deutschland: Das letzte Tabu or mein Leben als Escort who will be there. And we will have curators from the Biennale of Istanbul here as our guests to talk about the practice of art in Turkey.

A: It’s an exhibition format which hopes to stimulate a discussion. For me above all as a practicing artist these events are platforms which produce an exchange about form, the artistic base, political events or whatever. This project is loaded with a message; all of the artists are loud, screaming an agenda about their works to the world. In the end it’s just a small beginning. Maybe this project needs to be overcome in order to be able to reappraise it a couple of decades later.

E: Primarily this exhibition has the potential to provoke a dialogue in German society. I look forward to seeing other projects inspired by and focusing on this part of German history, as well as others.

What moved you most during your preparations for the exhibition?

E: Above all friendships which started here and the trust of the artists. It has given me the opportunity to think about migration in another way. Not just as a curator but as a human being.

In your press release it says, “It (the exhibition –ed.) looks into a queer-migration mood typical to Berlin.” How exactly is this expressed compared to other European cities?

E: When I studied film at the Bauhaus University in Weimar, I didn’t notice a specific queer or multicultural vibe. I met a lot of young students, but they came and went. In Berlin, you can smell migration history on every corner.

A: And you can still afford to live in central areas. This also provides the migrant community with a chance to access the city more than elsewhere. For me, as an example, Amsterdam is a fairly divided city where the centre is inhabited by the white middle-class. And we can say the same about Paris or Stockholm with their decades of gentrification. Die unfortunate division of the city, which Berlin had to go through, however, has created different perspectives for urban life. And the queer museum is situated here in Schöneberg, where the big migration in the 80’s began. Nowadays, it is home to the biggest night life LGBT+ scene in the city. This makes the atmosphere so special here.

Could you imagine organizing something like this in Turkey right now?

A: Why not? There were always difficult times in Turkey, because censorship never disappeared totally, not even after the end of the military state. And it can change again in 10 years’ time – who knows. In all the decades, there was always an intention to liberate. For example in the 90’s, when the war against the Kurdish nation reached the critical stage, I remember the performance of a female Kurdish artist. She walked naked over to the corner of the room. She squatted there for a while. After she left, we saw that she had left some of her menstrual blood on the ground.

Can you imagine that happening in times like these?

Well, I would say that art is possible under any circumstances.

You can find the whole exhibition program here

Translation: Melise Eren