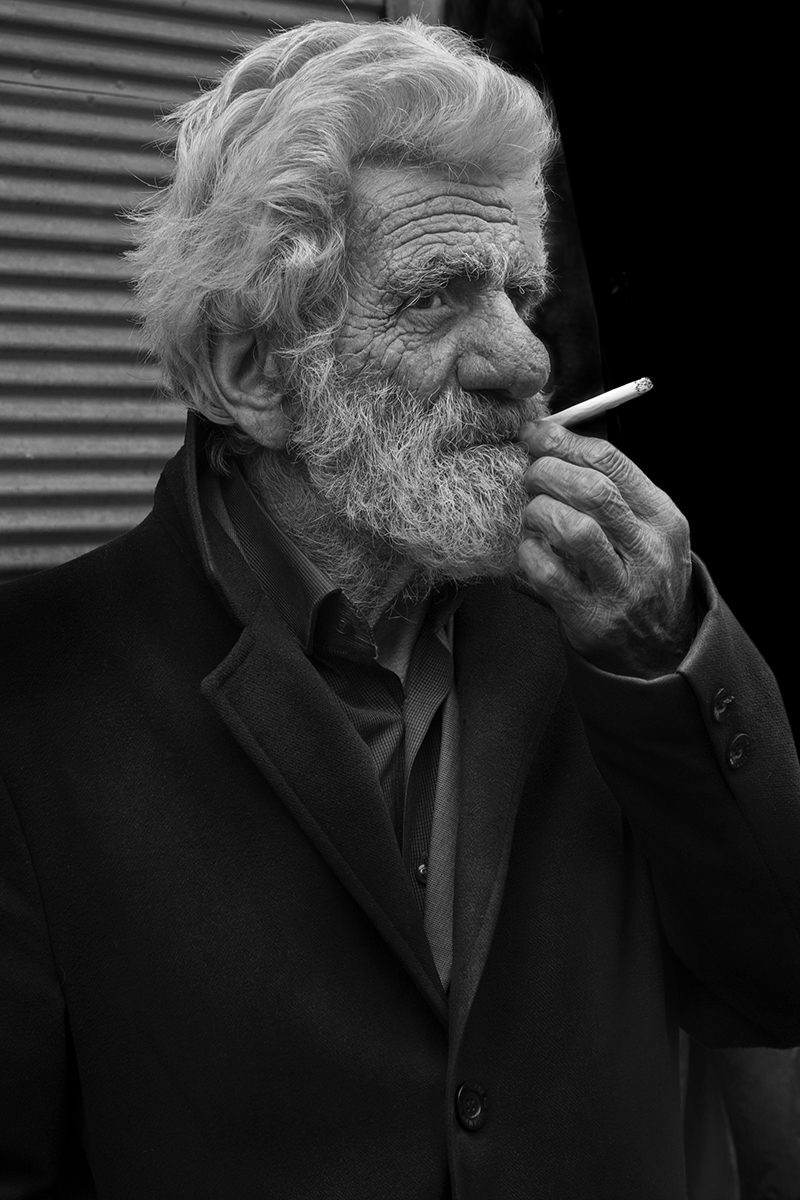

Ralf J. Diemb has been taking photos since the eighties. He lives in Ettlingen / Wilhelmshöhe, and in 1983, he founded the studio community Wilhelmshöhe with fellow sculptors, painters and writers. Two years later, it transformed into an art association. Since his retirement in 2007, he has been able to focus on photography once again. With his photographer friend Sadık Üçok, he accompanies people via his social documentary photography in Turkey.

Ralf, which connection do you have to Turkey?

I have been friends with Sadık Üçok, a Turkish caricaturist and photographer, since 2012. I regularly meet him in Istanbul., and we have already put together four exhibitions in Germany

When was the photo series “Hayat” created and in which context has it been presented so far?

The project started in 2012 when I visited Sadık for the first time in Istanbul after meeting him on a social network. We quickly agreed to observe life on the streets of Istanbul and to capture it as a social-documentary. Sadık has been active as a street artist in Istanbul since the 1970s. Until now, our photographs have been shown in these four exhibitions in Germany, in which each exhibition of course has been supplemented by a new selection of existing photographs.

Hayat is Turkish and means life. Which lives do you accompany with your camera?

Because of the fact that the old city districts of Istanbul are disappearing, almost all of the old wooden houses have already fallen victim to the excavators and have been replaced by sterile architecture, we began to observe the life and circumstances of the people in these city districts and capture it visually. Ara Güler said once, “Time may turn cities into dust, but human dramas will be alive for centuries.”

What do you think of nostalgia?

I am a friend of everything nostalgic, and love it when traditions are lived and preserved. A week ago, Sadık and I took pictures in craftsmen’s workshops in Safranbolu, a UNESCO World Heritage in Turkey. We met shoemakers, iron smiths, silversmiths and carpenters, whose workshops were adventitiously dilapidated on the edge of a gorge, as if they were stuck there. I felt liked I’d gone back in time a hundred years.

How do you find access to people you want to photograph? Do you speak Turkish?

First and foremost, street photography lives on spontaneity. I think of Henri Cartier Bresson, who said, “If you don’t ask, you’ll get a good picture, if you ask, you may end up having to delete a good picture.” Over time, I have picked up a lot of Turkish vocabulary, especially some important short sentences. This helps me in difficult situations, particularly if I want to take a specific portrait. So far it’s worked out well.

Why did you photograph your series “Hayat” in black and white? Life has so many different colours.

The world is colourful, but black and white fits my fantasy! The viewpoint and the concentration on the essentials are what make black and white photos so special to me. When I watch old films such as Casablanca, Don Camillo, Damned in All Eternity or the Third Man, I can’t even imagine a new production in colour; it comes across as too expressive

In which city districts of Istanbul did you work as part of “Hayat”?

Sadık and I mainly roamed around the old districts of Balat, Fener, Samatya and Kadırga. We also spent hours at the Galata bridge and on İstiklal in Beyoğlu.

What makes the districts where you took photos so special?

In these districts, the people’s lives are still authentically traditional – they are places not commonly frequented by tourist. I come into contact with forms of work and life which are in the process of disappearing.

Is gentrification a topic that you have dealt with mentally or photographically?

This aspect inevitably plays a role when I see how the old city districts have changed since 2012: the old wooden houses are disappearing from the cityscape, entire city districts like Tarlabaşı, Suleymaniye or parts of Fatih are rented out and fall victim to a rapid and recklessly advanced modernization.

What did you experience while you photographed Hayat?

I have consciously experienced how a city loses its flair and unmistakable charm through a rigorous and callous urban planning. Markets like the fish markets in Karaköy and Kumkapı had to give way to a parking lot or construction of a new underground. Starting a year ago, for example, there are new ships which travel from the Asian part of the city to the European side, and they look like floating hotels or huge bathtubs floating on the water. Gezi Park, the only green area in the city centre, is to be replaced by an oversized new building according to the wishes of the city administration and the president. I experiences a similar transformation to a more and more faceless high-rise metropolis years ago in Singapore, when the Chinatown there was razed to the ground.

Credits

Photographs: Ralf J. Diemb

Translation: Melise Eren