This summer it was time to visit my parents’ old homeland. No, not by plane. It was time to do it old school style. By car like in the good old days, across the Balkans with kit and caboodle and everything that goes along with it, we were about to travel to the country that had just thwarted a military coup. It had been five years since I had been there last, and twenty-six since I’d done it in a car.

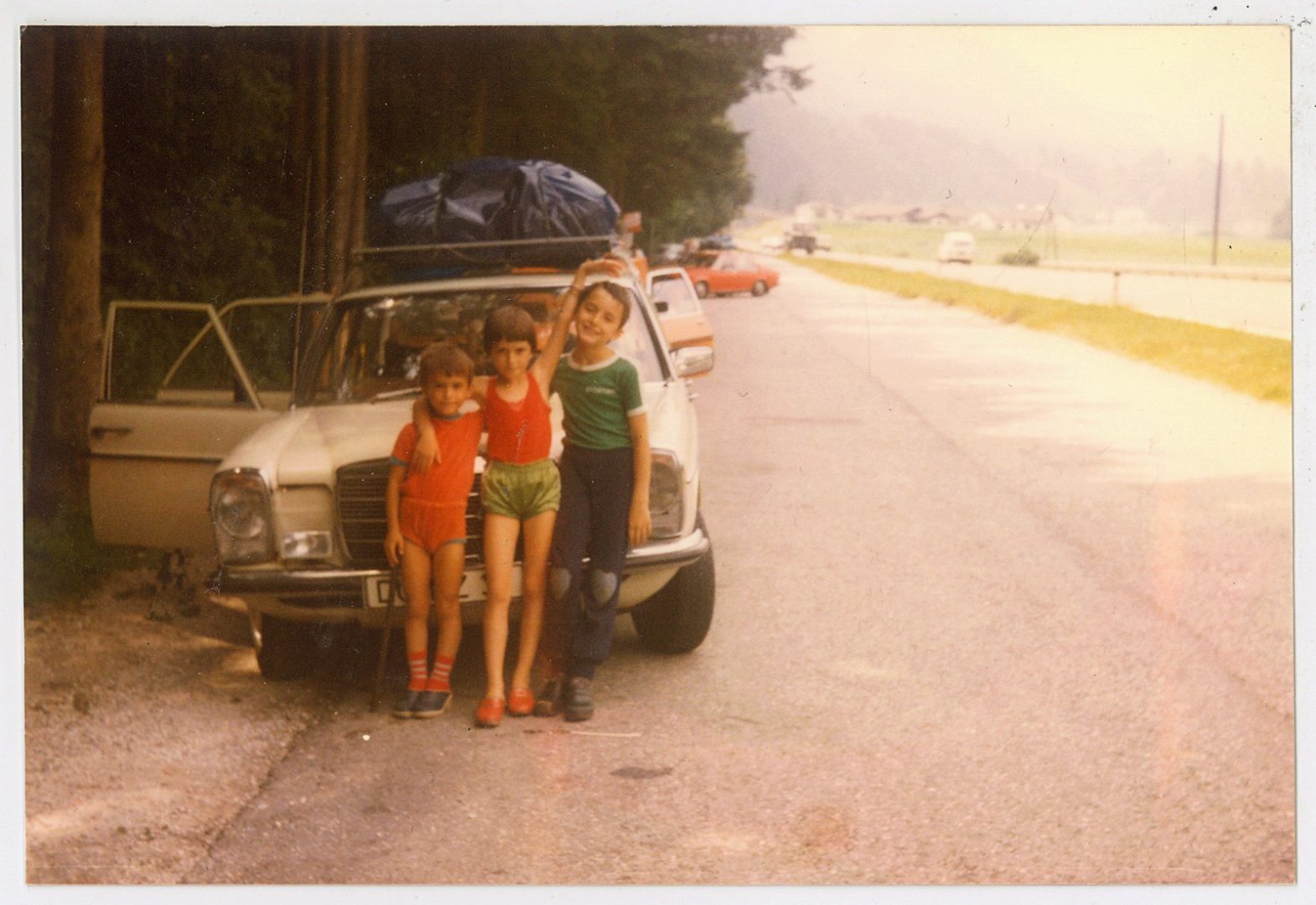

Back then, the 13-year-old me sat in the back seat while Baba drove. This time I was the baba in the driver’s seat.

For that reason, it was a special trip, at least in my eyes, because it was time to show the children where their babaanne and dede actually came from, and how far that is from us here in Berlin.

We decide on a 3000 kilometre-long route to Tekirdağ, the former fishing city on the Marmara Sea 134 kilometres west of Istanbul. To me, the Balkan Route to Turkey was always the route that combined old and new and held them together. The route where every kilometre showed me how hard arriving and leaving can be; the route thousands of people from Europe embark on each summer in order to travel back to where they originally came from. However, we weren’t in as much of a hurry as my parents were in the days when they used to fly along the motorway each summer, only stopping for short breaks in order to get some rest or go to the bathroom.

After a ten-hour drive, we spend the first night in a semi-private guesthouse in Slovenia just beyond Ljubljana, and the next evening we pitch our tent across from a dreamlike island in northern Croatia. Our goal is fixed, but we don’t have a concrete travel itinerary, since we aren’t sure how far we will get each day, or how long we can expect the children to travel.

Two weeks have passed since the attempted military coup in Turkey and my stomach turns when I think about the political situation there.

If something else bad is going to happen, then it will probably happen soon. The more time passes, the more stable the situation will become, I hope. After three nights, we take down our tent in Croatia and slowly work our way along the Mediterranean Coast. Shortly before Dubrovnik, we decide spontaneously to search for a place to stay.

The next morning, after a nice chat with the young hotel manager, we continue along the coast towards Montenegro. Before we get there, we still need to pass through the thin strip of land which constitutes Bosnia and Herzegovina’s only connection to the sea. It is about 10 kilometres wide and is nestled between Croatia on both sides, marked by two border crossings. It takes us three hot hours in the car before we have passed through this eye of a needle. Subsequently, we treat ourselves to dinner in a fish restaurant in Herceg Novi, just after the border crossing into Montenegro. It is surprising how abruptly the topography changes here. Suddenly, we are surrounded by dark-green forested mountains – Montenegro is true to its name. The tourist industry is quite new here, the dense and lively coastal promenade was built with Russian funds and they weren’t stingy about it.

We noticed while paying that the Montenegrins’ countenances become quite annoyed when anyone attempts to pay with Croatian Kuna. It may stem from the cultural proximity to their Serbian-Orthodox neighbours, who still do not have much good to say about majority-Catholic Croatia.

The sky above us grows darker and we still have nowhere to stay the night. As we drive further southeast, we keep stopping in order to search for accommodation. Yet we are out of luck, and the children become increasingly grumpy. Quickly, we drive along the winding road – until a police car flags us down from the side of the street. “Oh no, that’s all we needed.”

“Because of the children …”

“Hello,” I say.

”Your light is broken,” says the policemen.

“Shit!” I think and get out of the car. It’s true! A dipped beam in the front has packed up.

“And you didn’t have your belt on!” he says.

“Come on!” I say. He looks at the license plate and asks:

“Where are you travelling? To Kosovo?!”

“No! Not Kosovo,” I say, “Turkey.”

He appears surprised.

“We’ve come from Germany. I didn’t know that the light was broken,” I explain.

He takes another look into the car and sees the children sleeping.

“I won’t give you a ticket, because of the children.”

“Thank you!” I say and smile at him.

“But! You have to fix that light before you drive on.”

“Shit!” I think, because it means our trip is over for now.

I drive back to the petrol station behind us, turn off the clattering diesel engine, breathe deeply and rummage around for the instruction manual in the glove box. Armed with the correct light bulb label, I go to the attendant’s box, which is empty.

Back in the car, I watch the police officer through my rear-view mirror as he energetically swings his signalling disc back and forth. I whip out my smart phone and try to get on the internet. It must be a sign! Five kilometres ahead there is a vacant apartment. Light shines on the “Black Mountain!” I see the petrol attendant enter his box. I just have to get the light bulb repaired and we’ll be on our way.

“Turn around!”

When I open the bonnet and see the complex panelling of the light, I feel sick. “Shit,” I think. “You’ll never figure it out – a damn Ford!” Dear nice cop, don’t be mad at me, but I’m going to drive the next five kilometres without the dipper light, I think. Because of the children, you know? He’s got to understand that. The somewhat weak regular light is still working and I’ll fix the other one tomorrow, I promise.

I enter the address into the GPS. It says we should go back the way we came, past the police officer. So we do. I start the engine, turn the car around and drive back. Back past the control point, but on the other side of the street. The policeman is busy and doesn’t notice anything. Phew! Relief.

But the problem with these GPS’ is that they are sometimes wrong. Because all of a sudden, she says, “Turn around!” I really hate this voice, there is something heartless about it, something inevitable. “Turn around,” she says again. My girlfriend and I look at each other. We don’t know if we should laugh or cry. At least the children are sleeping. I drive further as if nothing has happened. Hopefully the GPS will stop acting up and suggest a different route. “Turn around,” she says, over and over. So we’ve got to pass by our nice policeman once more. But who knows how nice he will be when he sees that I didn’t follow his instructions. The evil transit tourist. What can you do, I think, and turn around. “Seven kilometres to your destination,” says the woman. “Just wait,” I think. About five hundred metres ahead is the same police control. Neither of us is in the mood for a discussion, a fine or for repairing anything in the middle of the night. We just want to get to the apartment, finish off these last five kilometres, put the kids to bed and go to sleep ourselves. Right before the control, the same police officer stops someone else. We slide past without being noticed. Dead lucky! Thanks, “Dark Mountain (Montenegro).”

To be continued….