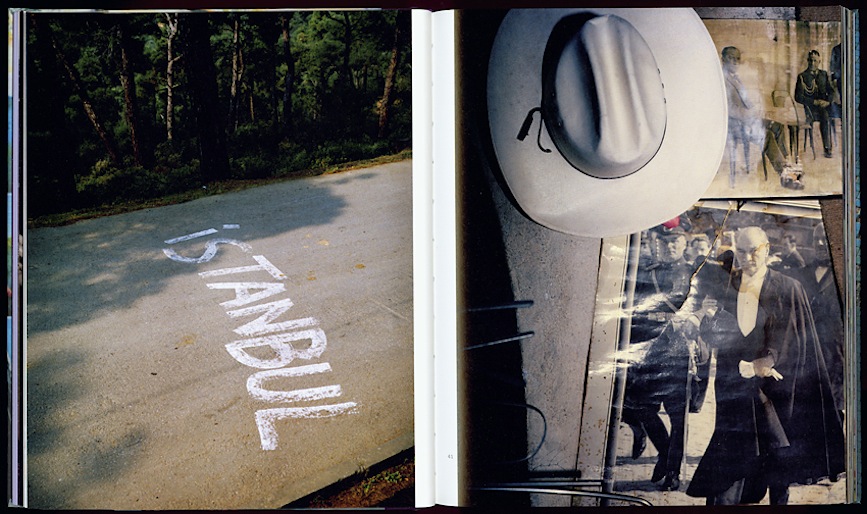

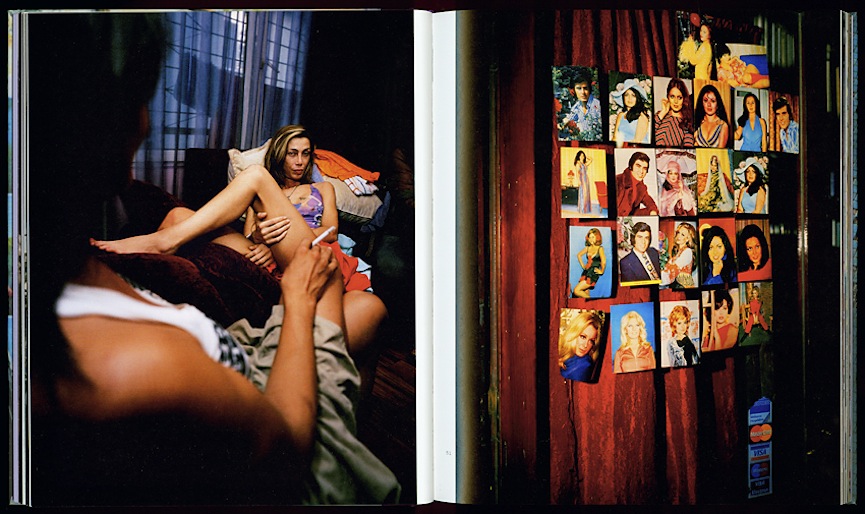

When I found Karsten Kronas’ photobook Beyoğlu Blue on a shelf a few months ago, I couldn’t stop thinking about it. For a start, I’m fascinated by the transgender scene in Turkey and I wanted to see who else there was apart from Bülent Ersoy, the diva of classical Turkish music. I also found myself wondering how someone had managed to gain access to this subculture. I admire Karsten for having the courage to show photographs of things you don’t normally get to see. Using colourful, high-contrast imagery, he portrays transsexuals living in Beyoğlu in a poetic way. Kronas studied photography at the University of Applied Sciences Bielefeld and the Marmara University of Istanbul and now works as a freelance photographer. His work has appeared in magazines and journals including Dummy, Greif and Slanted. In 2011, he was nominated for the German Photography Prize.

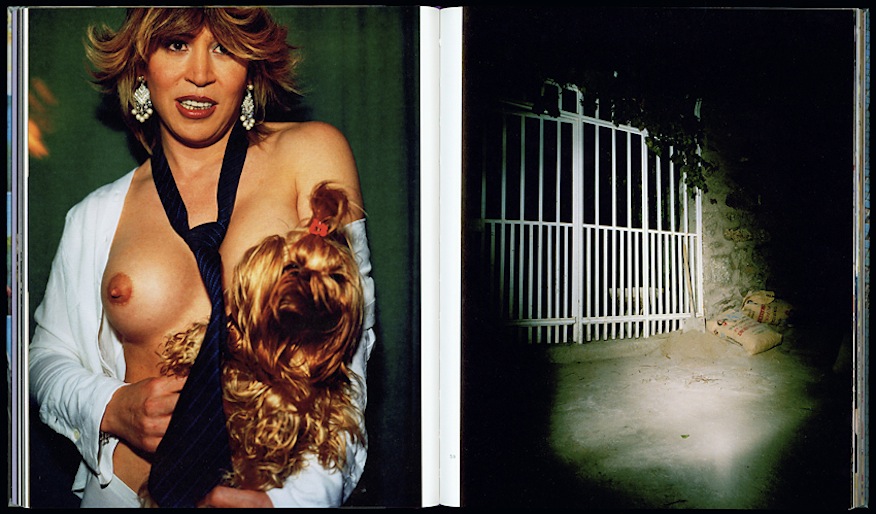

Amongst other things, your photos illustrate the underground transgender scene which very few people get to see. Why did you decide to choose a topic that is such a »taboo«?

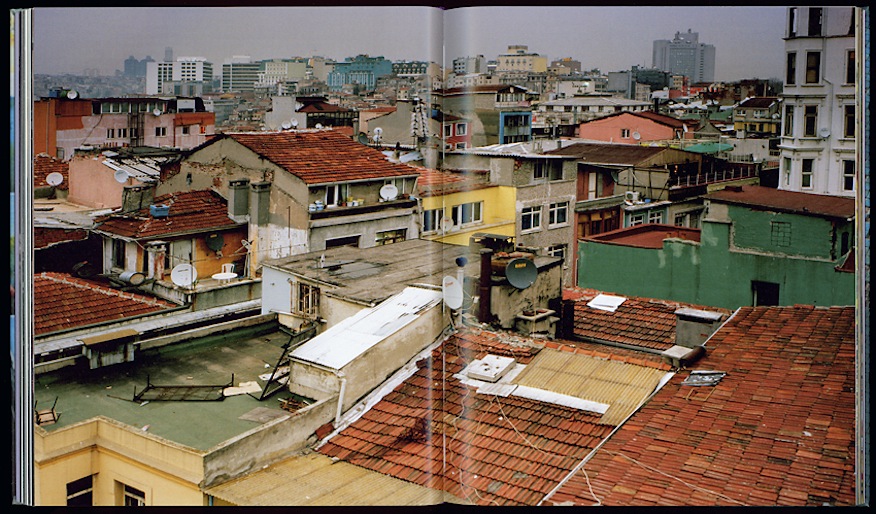

I never really felt that transgender people were living in the »underground«. To me, they are an essential part of Beyoğlu and that is how I approached them. When I was in Istanbul for the first time in 2003, I was surprised how western Turkey seemed. Over the next two years, I would often question my view. As far as I was concerned, the transsexual culture was a bold form of »revolution« and I wanted to learn more about how those involved experienced and perceived Turkey.

It took a couple of years for me to realize that I was addressing an issue that was a taboo – that happened when I was asked to exhibit the series in the Stadt-Galerie in Mannheim two years ago. It was a curated exhibition together with another German photographer and a Turkish photographer from Beyoğlu, and was held to celebrate Mannheim and Beyoğlu being twin towns. Initially, we were going to exhibit together, but apparently the Mayor of Beyoğlu and the delegation that came with him were affronted by my photographs, so my vernissage was brought forward by two weeks. Two weeks later, during the official opening, some of my pictures were removed in order not to offend the Turks.

I have often heard it said that it is really hard to get in touch with transsexuals. How did you manage to enter their world?

It really did take a bit of time and extra work in advance to build up the right amount of trust; this was because I looked for contacts within the scene and not via an association. But for me that seemed the most compatible and more honest way.

Can you describe any times when you saw yourself heading towards danger?

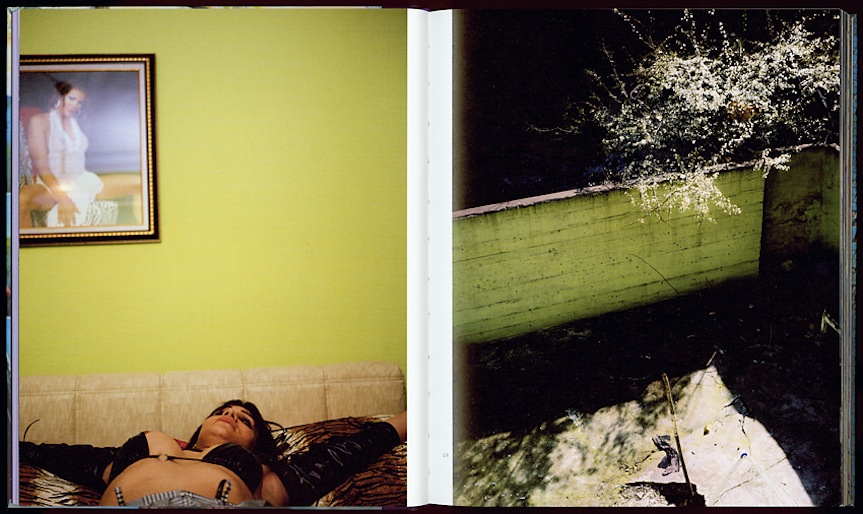

When I began to work on the project, I automatically had to seek out the back streets of Tarlabaşı where some of the transsexuals live. These streets below Taksim Square aren’t pretty, but I was aware of the risks. It was more dangerous inside closed flats, because then you are exposed to the clients.

Is there a reason why so many transgender persons earn their money with prostitution?

As far as I can see, it is to do with a social model based on class and usual prejudices. Most of them have no money and are valued accordingly. Bülent Ersoy, one of the most famous pop stars in Turkey, doesn’t have any problems in her career because of her transsexuality. But there are some people who see prostitution as an easy way to make money.

Did you hear stories of misfortunes that affected you personally?

I often had the impression that their lives are a chain of misfortunes and it wouldn’t have felt right to suggest that I could really understand. There were moments when it was very hard to share their personal fate and I would find myself feeling like crap.

You’ve said, and I’m quoting you here, »Rules and dogmas of a predominantly Islamic society recede and the abnormal becomes normal«. Has your perspective in terms of normal and abnormal shifted because of your work?

I wouldn’t say that my perception of normal vs. abnormal has changed. But more and more, I try to avoid putting things into categories if I can. However, assuming that there is such a thing as morality, then a sensitivity for the double standards in Turkish society has crept in since. »Millions of homosexual men, gays argue, although they are the true heirs of the Ottoman tradition, have been suppressed during the course of Westernization, and lead a life in the underground in constant fear of discovery … « Deniz Kandiyoti, »Call me Istanbul ist mein Name « (engl. Call me Istanbul is my name – ed.) (eds. Roger Connover, Eda Cüfer, Peter Weibel).

What expectations did you have when you travelled to Istanbul and what did you learn?

In 2005, I travelled to Istanbul to find answers to the questions posed on my first trip in 2003. I did find some answers, but I returned to Germany with a lot of new questions, so I went back to Turkey again in 2007. That’s when I started to work on the »Heterotopien« project.

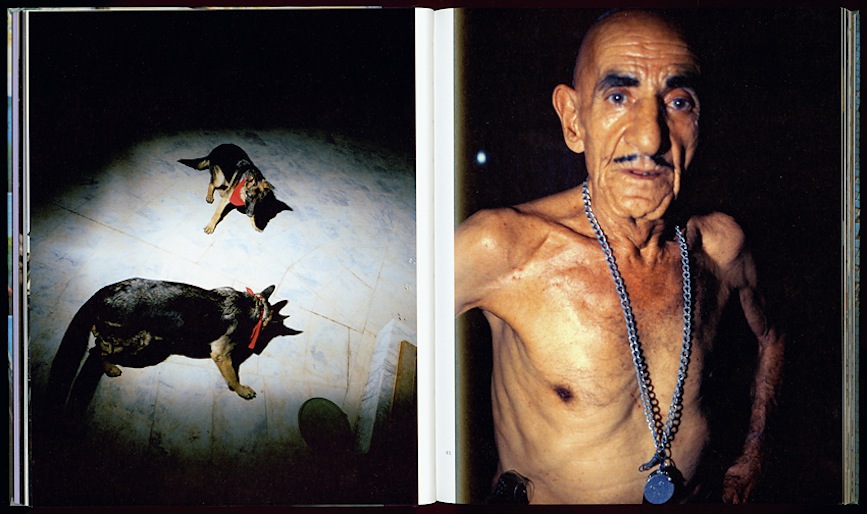

Your photography is very vibrant, colourful and full of contrasts – do you hope to convey a certain feeling? And if so, what would that be?

Thank you! I am always really pleased when people can see it that way. The level of colour is one of the constants in all the photographs, and it’s a device to up the drama a bit. I think that, initially, the colours trigger emotions, but then the story emerges when you add up the content.

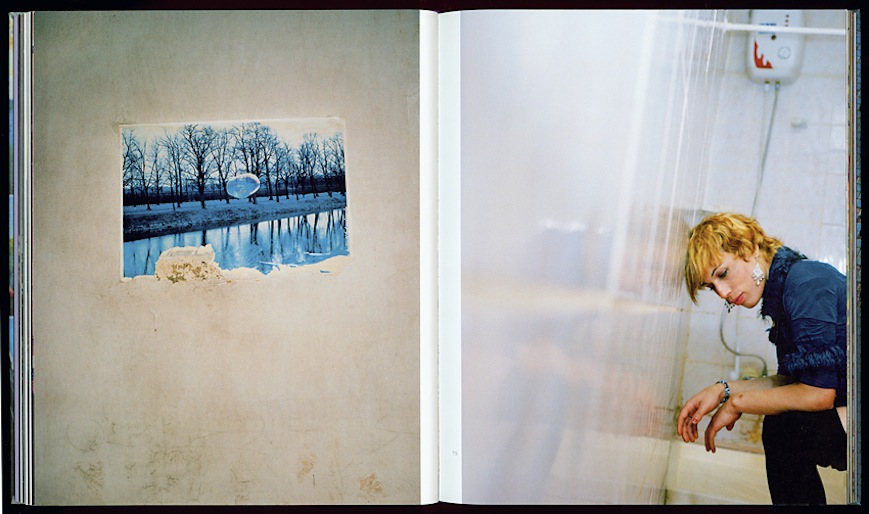

Would you say that you stage your photography or is it documentary?

It is definitely not documentary. I work far too conceptually for that – even if it’s no more than simply combining photographs in a certain way. But it isn’t really staged, either.

How long do you accompany your portrait subjects before you have created an atmosphere in which you can take an authentic picture?

During this project, most of the portraits were taken really spontaneously and the atmosphere was based on mutual trust. I spent far more time preparing the detail shots.

Which of the photos from the »Beyoğlu Blue« series is your favourite picture and why?

That changes all the time, especially as I keep on finding new images on the contact sheets that I hadn’t noticed before. The picture with the soap bubble floating across the regulated river is one of my favourites – together with Sibel sitting on the toilet resting her head against the wall. I also love the picture with the wilted tulips and some fresh ones, which can only be seen as a print on one of the flower pots; and the image of the heart is one of my favourite metaphors within the series.

Did you follow a guiding line which helped you select the photos? And if so, what was it?

It’s hard to say. This project was allowed to unfold after my graduation, so there was never just one central theme. The series went to Australia as part of the »Hijacked Vol.2« project on Australian and German contemporary photography, where I found it especially difficult to limit the number of photos to just a few. At the Lodz Photography Festival in 2011, it was shown in the main program and I went back to the lab and discovered several new images and new combinations. In the Stadt-Galerie in Mannheim, it was shown as part of the program celebrating Mannheim and Beyoğlu being twin towns. I am absolutely delighted that this project has been able to continue to develop.

When do you regard a series of photos as completed?

There isn’t a simple answer because of the way I work. As far as this project is concerned, there could well be a second volume in the offing because there is so much material.

Karsten, thank you for answering all my questions. l can’t wait to hear more about your work.

There is more information about the book by Karsten Kronas here.

Fotos: Karsten Kronas