We met Nezaket Ekici in her studio in the Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin. The artist has performed in many parts of the world, and her work has been displayed in several high-profile galleries and museums worldwide. Sitting on a large oriental rug spread out in the middle of the room among materials, books and coffee, we discussed her performance art. The rug that we sat on represents a comfortable “coming-togetherness” and was used as part of one of her works.

The rug that we are sitting on was part of your installation in Dresden in 2015. There were reports in the media that it was damaged and smeared with far-right slogans. What happened?

In 2015 I was invited by curator Thomas Eller to prepare a public art project for the city of Dresden. I had never been to Dresden before, so I wanted to explore the question of whether Dresden is tolerant and open to different people and cultures. I was aware that an Egyptian woman had been brutally murdered in an act of xenophobia in front of the Dresden State Court. Her story affected me deeply, so I decided to erect a portal made of 34 oriental rugs in front of the court building. Not too long afterwards, I got a phone call from a journalist who informed me that the installation had been damaged. Within the space of two months, thirteen of the rugs had been stolen. The rugs had the words “Scheiß Islam” (the English equivalent is close to “Fuck Islam” – ed.) smeared over them twice. The police took the vandalised rugs away without informing me about it first, which destroyed the artwork. That made me very angry. I also had to constantly replace the stolen rugs or hang the artwork up in a way that would make the graffiti invisible. I went to the police six times and could not find out anything about the perpetrators. I felt abandoned.

Did it affect you personally? How did you deal with words like “Scheiß Islam”?

It annoyed me, of course, but it did not really have so much to do with Islam. These rugs are not only found in Islamic spaces. Oriental rugs are important objects that can also be found in many middle-class homes. They’re a well-established part of Western culture and are not “foreign.” As such, I wanted the primary focus to be on the beauty of these rugs and not on Islam. For me, it had more to do with culture than religion. However, I had not expected the rugs to cause the reactions that they did in Dresden.

Your art continues to trigger controversial reactions. For instance, you have also dealt with religious taboos in your work. Do you enjoy being provocative?

The reactions from the far-right are just one of many examples. I enjoy working with symbols and I know that that can be provocative. Sometimes I touch a nerve and that results in being rejected from different circles. Whenever I use religious taboos and symbols in my work, I expect there to be strong reaction against it. Pigs, for instance, are a symbol that I explored early in my studies.

Why pigs?

I was interested in exploring the question of why pigs are considered bad and unclean in Islamic circles. That is why I wanted to explore the issue much more closely. In early 2004, I had the opportunity to work on this topic for the first time at the MARTa Herford Museum, and I suggested to the curator that I would go into a pig-pen wearing a burqa and perform my exploration of pigs live in front of an audience. Unfortunately, the project was rejected for fear of fundamentalism. My work about pigs has constantly been censored and suspended. Only in 2007, at the “Türkisch Delight” exhibition at the Städtische Galerie Nordhorn, was I able to perform my pig performance live for the first time. There was even a hodja (Islamic religious scholar) in the audience.

How did the hodja react?

After the performance, I had the opportunity to speak with the hodja. I got the impression that he understood what I had done on stage. Otherwise, he thought the performance was fine because I had gloves on and did not touch the pig directly. In his eyes, I did not violate Islamic rules with my performance.

You work with symbols as a way of questioning religious taboos. You have also done that in Muslim countries. What have the reactions been like there?

They have varied. I remember two different moments in Syria and Mardin. In 2003, I was invited by the Goethe Institute in Aleppo to perform my work “Emotion in Motion” at the 5th International Women’s Festival. In that performance, I kissed a room full of personal objects with heavily painted-on lips – all while dressed in a white negligée. Quite erotic, really! The curator and I had the idea to perform the work in a completely glazed hotel lobby, so that people walking past outside could also take part. Within five minutes of the performance beginning, the police came and we had to stop. The curator then quickly moved the performance over to a private gallery, but there I was only able to perform in front of a very small audience. That was difficult to deal with.

And how did people react to your work in Turkey?

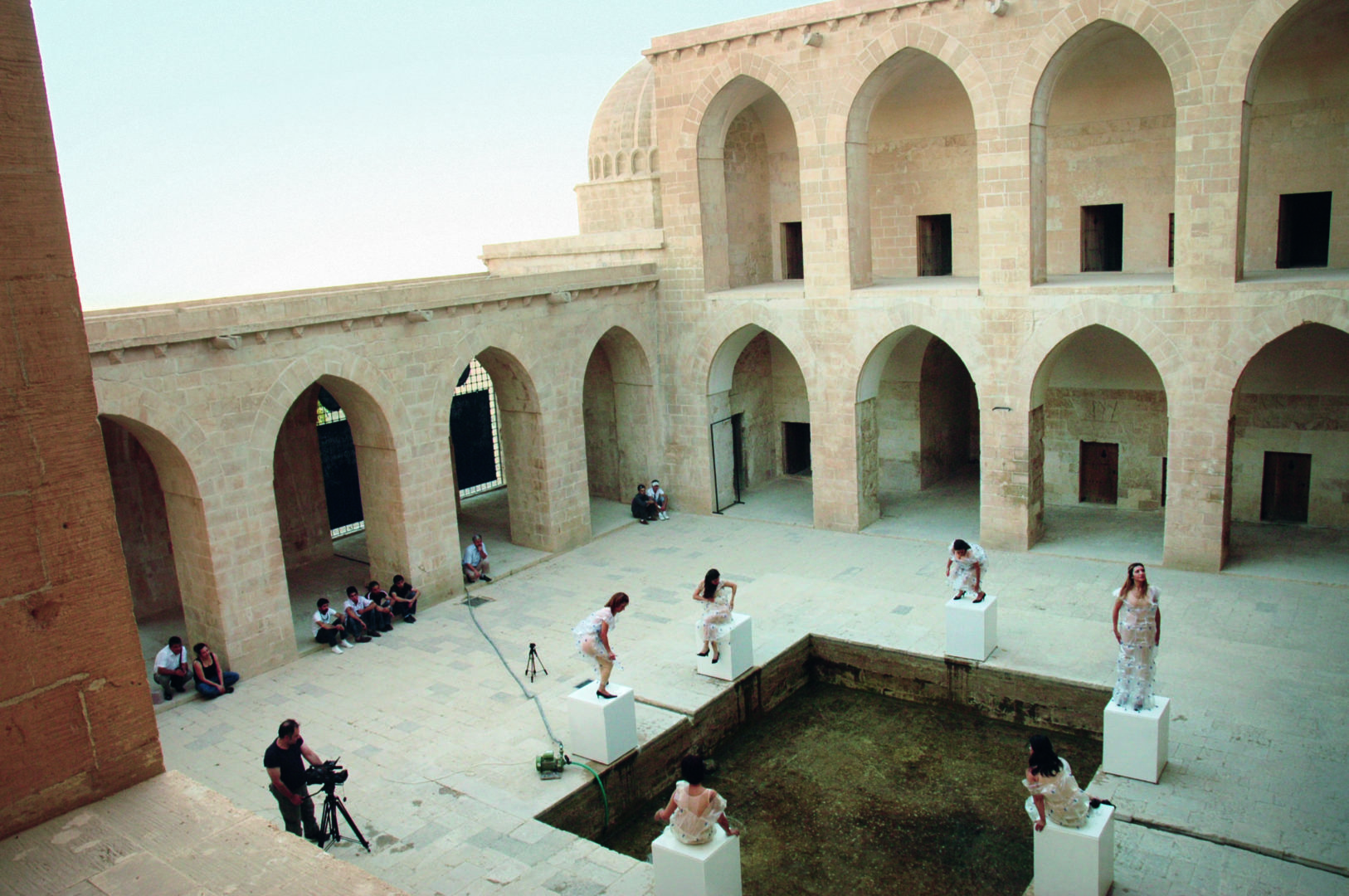

In 2010, I performed in Mardin, in the east of Turkey, and there I faced problems like I did in Aleppo. For my project “Fountain for 6 Women” I prepared a performance together with six local Turkish female teachers. It was clearly too provocative for both the city and the Turkish media. We performed at an historic location at a university in Mardin. There, we stood around a water basin on pedestals and let water flow from transparent urine bags on our bodies into the basin. Under the urine bags we were all wearing colourful clothing. However, the mayor of Mardin thought that we were naked, and was not able to bring himself to come and have a quick look. Others left the event. The performance itself was not cancelled, but the Turkish press stirred up hatred towards me and created a scandal out of my performance. It was simply too provocative for many Turks in Mardin and across Turkey.

How strongly are you able to identify with Turkey after such experiences?

First and foremost, I am a human. Living among several different cultures is difficult – incredibly difficult. Most of the time you never know where you belong. I am happy that my father gave me the opportunity to get to know a second culture, but for me it’s not really about German or Turkish culture. I have a third culture, and that is art. It is my language. I do not just work on German-Turkish issues, and I would not like to be labelled a “migrant artist.” Above all, I work on topics that simply move me. Usually I have an idea and put it into practice, and this often touches on social issues that relate to everybody.

Your latest project is about the commandment “Thou shalt not kill”, which can be found in all three of the main religions. How exactly have you been exploring this?

Nowadays, killing has becoming something of a game. Whenever we watch the news, we continuously see how violence has been increasing in all societies across the world – perpetual terror and killing. Therefore, I have asked myself what value the commandment “Thou shalt not kill” still holds today. In this project, which I have already performed in Norway, the commandment is mounted on to the wall in the form of water hoses filled with red juice. In the performance, I drink the red juice, which is meant to symbolise blood, from the hoses. This is very exhausting and takes a while. When I finish drinking the juice, the commandment’s value is no longer there. It becomes empty.

Translation: Kerim Onur Hassan