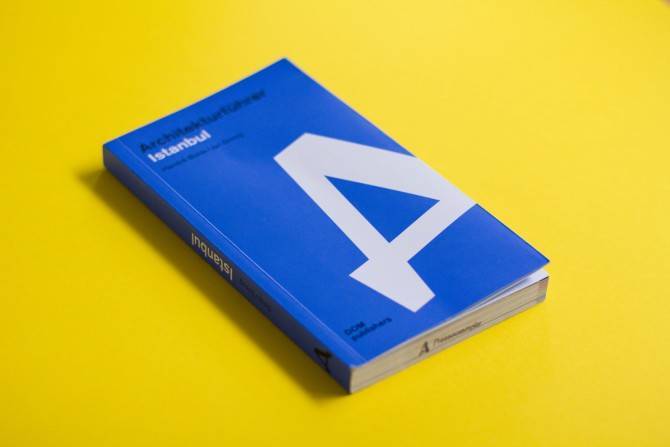

The Greeks called Istanbul »The City«, because the most beautiful city in the world had no need for a name. It is especially loved by flâneurs for its classical heritage and its culturally diverse structures. Many guidebooks are nothing more than a description of Istanbul’s historical monuments. They tend to present the city as an open-air museum. In doing so, the modern Turkish architecture movement is unfairly overlooked. This is why the »Architekturführer Istanbul« (engl. – Istanbul Architecture Guide) by Hendrik Bohle and Jan Dimog is unique, because it allows the reader to take an exciting architectural walk through history right up to the present.

»Istanbul, whose countenance

is beautiful and lovely like the

radiance of a tender saplingand whose water,

pleasant, light and delicious to enjoy,

resembles saccharine sherbet,whose soul-refreshing, musk-scented air

reminds one of the frizzy hairs

on the temples of their graceful lover,whose gazelle eyes are playful and

perfect, like the dark spot on

the cheek of a lover,and whose inhabitants wear visages

like those of Houris,

living in the highest paradise.«

(Enamoured Poet, 16th century,

from the book Istanbul by Klaus Kreiser)

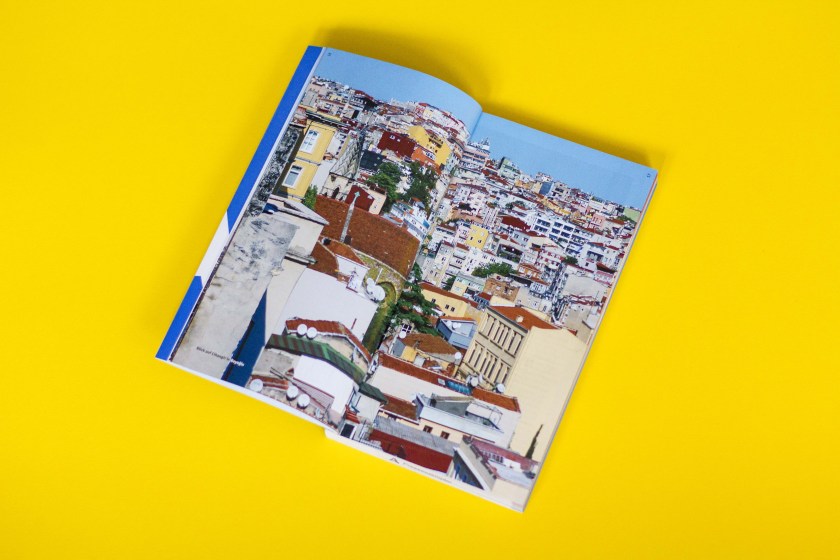

The historical peninsula’s dome-like landscape, with its minarets, the charm of its aromatic alleyways, the call to prayer, the patina of the old city’s façades, peddlers scurrying about, and the oldest bazaars of humanity are typical depictions in various Istanbul guide books.

Humans create the city, and then the city them.

Of course, a look at history is essential in a place that has been populated by humans for 2600 years. Still, the modern architecture movement in Turkey is gaining more ground worldwide. The urban understanding and interests are increasingly coming into focus for an emancipated civil society within Turkey. The awareness that plurality and the need for the civilians’ right to be heard are gaining importance, city planning included. Along the lines of the motto: »Humans create the city, and then the city them.«

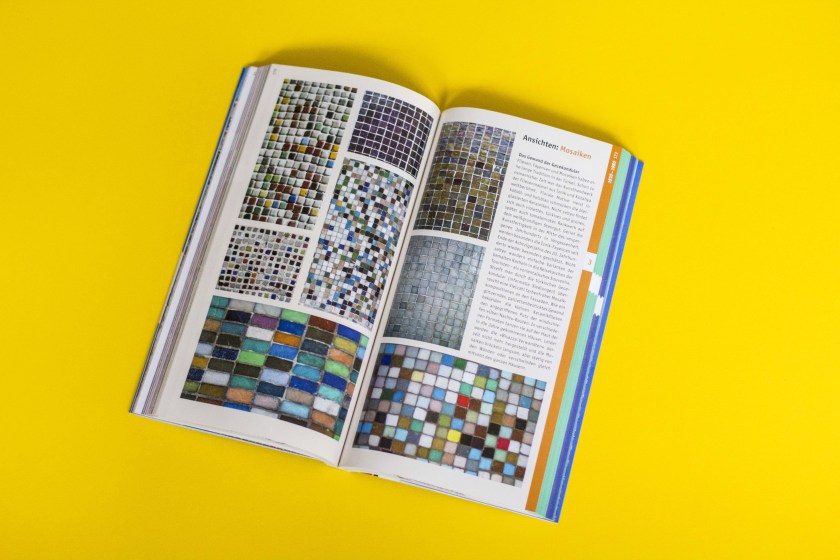

For this reason, many modern buildings contain traditional, earlier elements. Modern housing complexes have turned to Ottoman architecture, which is highly evident in current designs. The architecture movement in the 20th century in Istanbul is an especially exciting and historically notable period from a German perspective. It is characterized by mutual influences and cultural exchange. During the Second World War, numerous German academics sought refuge in Turkey.

At the same time, the young Turkish Republic was politically reinventing itself – modern, secular, open and sophisticated. Many German academics found a place in the reformed faculties and institutions of a new political-architectural orientation. German exile architects such as Bruno Taut, Ernst Egli and Paul Bonatz influenced the new cityscape of Istanbul and the new capital, Ankara. They left their mark on many Turkish architects, before international style took hold over time.

Today, the metropolis, which has grown to become a magnet for the entire region, represents a melting pot between Islamic tradition and open-minded, quite more emancipated city-dwellers.

The »Architekturführer Istanbul« (engl. Architectural Guide to Istanbul-ed.) playfully illustrates all of these depths, overlaps, and the architectural chronology, and accompanies the reader on a stroll through the multi-faceted eras: Byzantium, the Ottoman Empire and the Turkish Republic. The authors successfully bridge the gaps, from the great structures and masters of the Ottomans like Mimar Sinan, to the architects of the first and second national architecture movements like Vedat Tek and Kemalettin Bey, to the buildings of the young Turkish modernity by Sedad Hakkı Eldem, to the local architecture scene.

Interviews, or so-called »conversations«, are also included; interspersed throughout the guide, students and curators get a chance to speak. Notably, big stars such as Emre Arolat and Murat Tabanlıoğlu comment on current socio-political topics. Critical analyses of the current building boom, the gentrification of old city districts and urban-political action areas, above all during the Gezi Park Protests of 2013, round off the book without getting too lost in the theory of it all. An extremely successful architectural guide that uses clear language, accompanied by colour photographs, informational graphics and city and public transport maps.

Credits

Text: Hakan Dağıstanlı

Photos: Melisa Karakuş